We are all photographers of some sort. We capture our most important moments in life and most of us even make the occasional pornographic photograph in the privacy of our bedrooms.

It takes more than that to become a professional photographer. Some sign up for art or photography classes. I did some of that too, but I was mostly motivated by the desire to not participate in the daily treadmill we call social life.

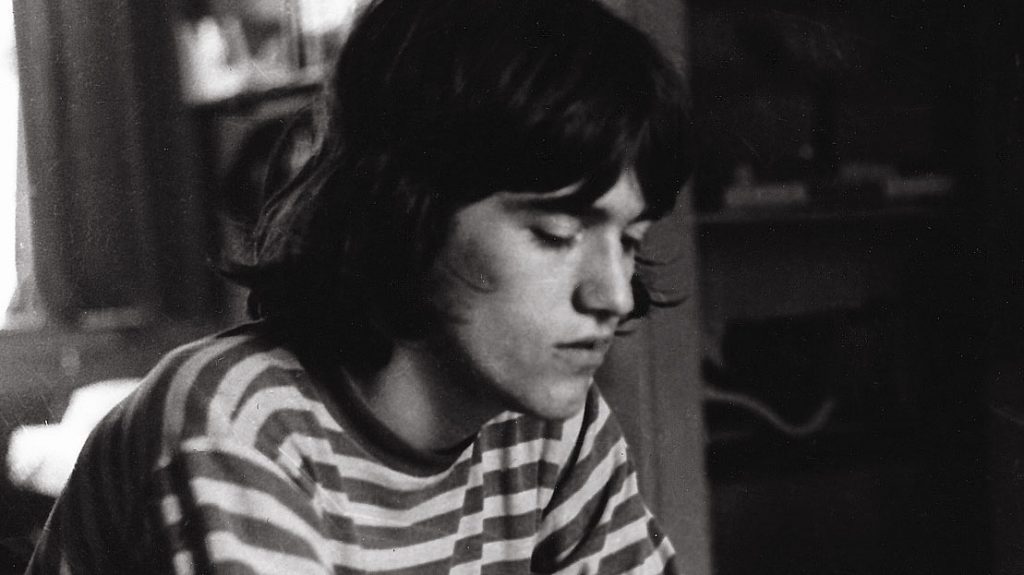

My desire was to look from the outside in. I was not a very well-adjusted adolescent. There was quite some trauma in my youth, which left me pretty inadequate in dealing with social events, so I brought a camera as a frame between me and others.

During school holidays I worked in a milk factory and I saved enough money to buy a very cheap and not so great Russian camera, called Zenith-E. The body of this SLR was great, but the lens was a disaster.

My father was a train enthusiast and an alcoholic. We had a hard time communicating.

I knew that I had to make great photographs of trains to get closer to him, so I photographed an awful lot of train scenes to please him.

This particular photograph was made in the winter of 1971, our last holiday as a family before I fled home at the age of 16.

Once I was on my own, I discovered photographing my girlfriend in harsh lighting conditions. The photo with dark black background, made in 1973 is the mother of all studio photographs I would make later on in my life. Of course, it was not made with professional lighting equipment, just with one bulb of 100 Watt, but I would stick to black backgrounds most of my career, simply because it puts all emphasis on the person portrayed.

Yes, despite all the nudity in my work, I look at myself as a portrait photographer. As I have often stated: ‘If a nose of the person portrayed tells us something about his or her character, why would any other body part be less informative?’

As a portrait photographer, I was fascinated by the many expressions people can have, but also how these expressions could be ‘enhanced’ by using make-up. This led me to do some occasional theater photographs, but I did not like the way the lighting was fixed, and I also had a hard time working in low light conditions with a camera that was not really equipped for those occasions.

In my job as an assistant photographer, I noticed that most top models had quite ordinary, yet symmetric, faces before make-up, only to evolve into perfect beings in front of a camera.

Once I saw this miracle happening in the studio, I lost all interest in documentary, candid and street photography.

Up to this day, I often get criticized for making people look better than they actually are, either by using very soft lighting or the use of Photoshop techniques. Well, I have very few arguments to counter these critiques, other than that I think that detailed reality in a photograph is highly overrated. It is not even what we see when we look around us. We see others in movement, and that blurs away much of the detail that we connect to ‘reality’. What we see, is not simply what our brain registers, we also interpret what we see.

Being bisexual in nature and fascinated by this alternate reality created in studios with make up and great lighting almost automatically led me to photographing transvestites, as they were called in the Seventies. Now we would either define this particular person as transgender or as a drag queen, or maybe even as a transsexual. I have no clue, since I have lost contact with Plumeaux on this photograph soon after I photographed her. I would continue photographing people who do not strictly define themselves as male or female throughout my life.

There is a wonderful article by Dionne Boekestijn about Plumeaux and my work with these people on the following address:

https://publicaties.zonmw.nl/fotograaf-hans-van-der-kamp-over-40-jaar-sekse-en-genderdiversiteit/

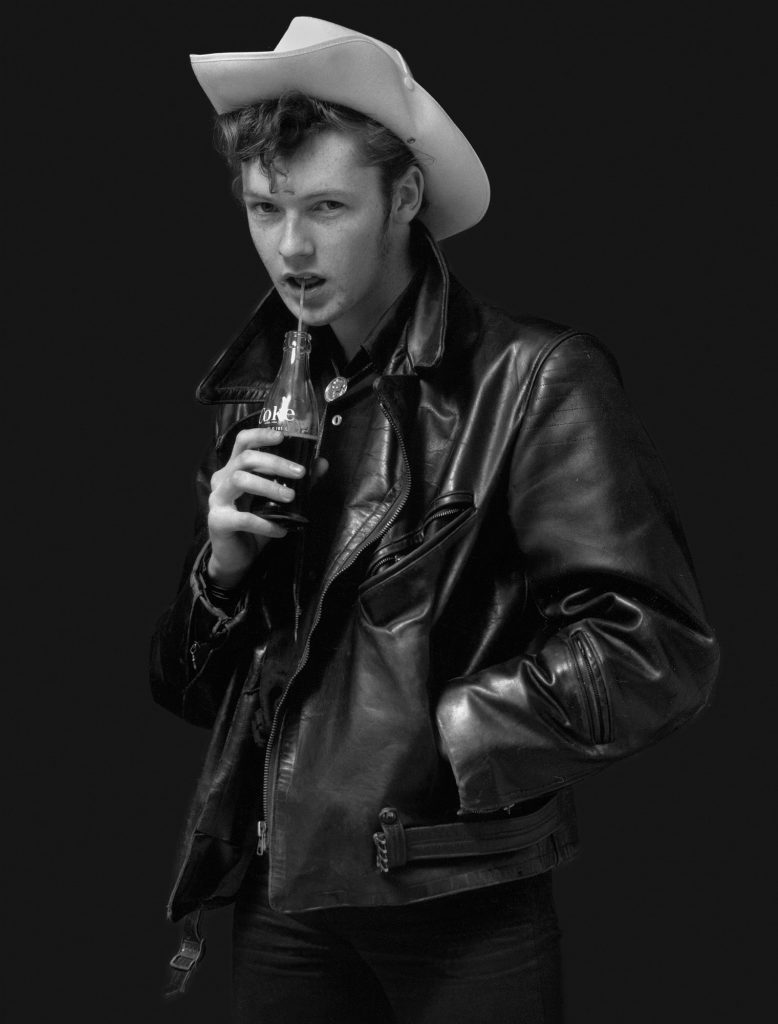

At age 22, after a few years of being an assistant photographer, I started my own photo studio. I managed to get a few assignments as a product photographer. While working on the Christmas catalog for a large shopping chain, I ran into some Greasers. A group of old rockers mixed with fans of the then popular movie Grease with John Travolta.

I could not resist the subject, and I embarked on a large project photographing these rockers, including stars of the 1950s such as Bill Haley and Charlie Gracie.

For this series, I had to learn how to direct people to pose for studio photography. Not really knowing what to do, I started out with a large mirror in front of my tripod and told the rockers to use that mirror as if it was their mirror in the bathroom and strike poses as they would before going out for a night on the town.

Much later, I learned how to give verbal directions to models. Yet, this first series became a success and I got my own solo exhibit in the Photo Gallery Cyclope in Brussels.

There I met a very famous Dutch photographer Paul Huf who advised me to contact weekly magazines with this series, and so I ended up working for Nieuwe Revu, a Dutch weekly.

I had forgotten all about the shopping catalog, and the people at the ad agency who gave me the assignment were not amused.

The studio was behind on the rent, so I had to leave it and I moved to Amsterdam to start working for the illustrated weekly.

There was not a lot of work for a studio photographer who hated working outdoors, or without controllable light conditions, but at times I did my best to work as a documentary photographer.

I recall having to photograph a street prostitute for a series on narcotics such as heroin and cocaine. I had asked a friend to join me on this assignment.

It may be very hard to understand for people who got to know me later in my life, but I was really too shy to talk to the prostitute. Instead, I photographed her in the mirror, with her back turned towards me, while she was doing her make up.

Once more, I could only deal with it all, by going back to my old theme of transformation.

In the end, the editor-in-chief understood that I was not the kind of photographer to send out on missions like these, and I refrained myself to studio photography from then on. I had to wait until I was about 50 years of age before I started feeling comfortable doing photography outside the safety of the studio.